The normal pace of everyday life may surprise those who venture to visit Damascus these days. From the city center with its vibrant markets, the idea that observers from the Arab League are visiting the city to investigate serious human rights abuses seems almost unreal. Yet, something has changed. In cafés and taxis people talk about politics, and though they do not do it at the top of their voices, such talk is no longer limited to hushed remarks. Massive explosions are disrupting the illusion that the city will remain untouched. And in the suburbs, there are demonstrations every evening that sometimes end with protesters being killed. The uprising is moving in on the capital.

We get a call – there is a “party” this evening in Harista, a Damascus suburb where people are taking to the streets because of unemployment and the humiliations that security forces have been dealing out for decades. Activists pick us up and we proceed to a so-called “safe house.” Five young men receive us in a living room brightly lit by neon lamps; the curtains are drawn and the air is thick with cigarette smoke. An older man joins us and the others greet him respectfully. Ahmad S. is one of the leaders of the protests in Harista. He explains that the recent attacks, which the regime blames on al-Qaeda and the protesters, have actually been staged by the regime itself. He asks why those attacks happened when they did, right when the Arab observers arrived, and why al-Qaeda never claimed responsibility. How was it that state television was on the scene of the crime right away? “They are trying to terrify the population and to portray us as Islamist terrorists.”

I ask him what he expects from the Arab League observers. “What is there to expect?” he replies. “Shouldn’t the mission be aborted as soon as another bullet is fired? Every day twenty, thirty, forty people are being killed. The only reason the regime signed the agreement is to buy time.” A young deserter from the Syrian army serves us tea. Some activists only leave the apartment every evening to join the rallies; others do not go out for days. They have not seen their families for months and switch residences every couple of weeks. The TV is tuned to “Orient News,” a Syrian Opposition channel broadcasting from Dubai. Here one can obtain an unfiltered view of the regime’s brutality. The coverage, filmed using mobile phones, is chilling: bones breaking under the boots of security personnel, backs showing streaks from lashings, and children in pools of blood.

The men smile when I ask whether the revolution can remain peaceful. One says that nobody was in favor of violence and that the revolution had remained peaceful for a long time. “But the regime kills our people. They shoot at women and children.” Still, there is no money to fight back, to buy arms. Ahmad S. takes an old revolver from a drawer beneath the TV; it is a Mauser. “How should we defend ourselves with guns like these?” he asks. He inserts a bullet in the cylinder, spins it, aims at the TV, and laughs. “This thing’s good for nothing but Russian roulette.”

We wait for a call from a driver who is supposed to get us to the rallies in Harista. The deserter looks out the window and is reprimanded by Ahmad S.: Doesn’t he know the curtains are supposed to stay drawn when it’s dark outside and they have the lights on? Finally, the call comes in. Ahmad S. gets up and explains to me how to get there. I am supposed to walk ahead of him by 200 meters. When we arrive, a small white car is waiting for us and Ahmad S. and the driver exchange news: Who’s been arrested today? Are there more dead?

The driver knows his way around. Avoiding military checkpoints, he passes underneath empty bridges, down partially inundated tunnels, and along unlit country lanes. Coming from Harista’s central square, a crowd of people is already on the move. Men from the Free Syrian Army are posted everywhere. Although insurgents are trying increasingly to smuggle arms into the country, thus far only the men of the Free Syrian Army know how to use them, my escort says. As the only woman in the crowd, I am asked to stay close to him. Should demonstrators take me for an informer, I might be attacked. A young man is leading the march. Others carry him on their shoulders, and through a megaphone he chants: “Down with Bashar now! The Arab League’s gift to us means slow death!” The march stops in front of Harista’s small Christian church. The leader chants: “Christians listen! Christians listen! We wish you a blessed new year. The Syrian people are one, be they Muslim or Christian. We are one, we are one!” So far, the Syrian churches are officially supporting the regime, out of fear that Islamic parties may take its place. Nevertheless, many Christians have joined the opposition. My escort explains how important it is to dispel their fears: “For decades the regime has told them that it alone will be able to protect them. In reality it is playing one religion against another and does everything to divide the people.”

Just after the march gets moving again, a shot rings out. The crowd scatters. We are carried along into hiding behind a car. More shots. My escort draws me into a shoe shop and immediately the shutters go down. Sarcastically the salesman asks, “what size shoes do you need?” and offers us a drink of water to calm us down. On the streets all is silent, but there is light visible behind the shutters. Ten minutes later my escort receives a call. Three demonstrators have been shot; six or seven have been arrested. The party is over.

We have to get out of the area, since it is beginning to swarm with security forces. Down a side street, another car is waiting for us. A member of the Free Syrian Army opens a small barricade consisting of nothing but an armchair and a traffic sign and shows us the way. Then he quickly disappears in a different direction. A man gets into the car with us and invites us to his house for tea. Mohammed U. is the leader of the Harista Coordination Committee. As we arrive at his flat, the power goes out. “This is how they punish unruly districts,” he explains. Since the protests began, power has been cut for hours at a time, and telephone and internet lines are being disconnected. In the dark living room, his small daughter holds a flashlight above my notepad to enable me to write. His sixteen-year-old son recounts how the security forces came to his school, arrested the director, and slapped a female teacher in the face. They also burned the hand of one student on an oven in order to make him admit that he had participated in a rally. Because of Mohammed U.’s activities, the son himself had been detained by officers and thrown into jail for a week. Was he tortured, I ask. “No, only beaten” he answers almost apologetically, as if beating does not qualify as torture. All of Mohammed U.’s brothers have been jailed as well. He asks, “Now, if a regime is really interested in dialogue and resolution, will it jail and torture innocent relatives and shoot peaceful demonstrators while an observer mission is in the country?”

The next day, we receive the news that a member of the Free Syrian Army will be buried in the Duma suburb of Damascus, and we decide to attend the funeral. Suleiman A., an activist from Duma, picks us up and instructs us: “I am being searched for, dead or alive. So should we get stopped, leave the talking to me.” I put on a headscarf, as Duma is known to be an especially conservative neighborhood, one where women even cover their faces. Suleiman A. is the owner of a leather factory, and was a preacher until he was suspended in 2005 for speaking about democracy in the mosque. I ask him at what point he joined the revolution. “Right away, on the 15th,” is his reply. Does that mean the beginning of the Syrian uprising in March? I inquire. “No,” he laughs, “on the 15th of December, when the revolution in Tunisia broke out.” Right from the start, it had been clear to him that the democracy movement would take hold in Syria as well. Consequently, he closed down his leather factory and went underground. His wife and daughter moved in with her parents. In order to support the family, his wife sells some of her jewelry now and then.

While a part of Harista’s population still supports the regime, Duma is almost united with twice as many inhabitants. Here, the first sit-in of the uprising took place, five days after protests started in Deraa. After a history of resistance against Ottoman and French rule, cursing the Baath Party has become a habit, Suleiman A. says. Duma was one of the strongholds of the Muslim Brotherhood, and when Hama was bombed in 1982, security forces arrested hundreds of cadres there. The regime cracks down on Duma more relentlessly than other places, he believes, because here they do not have supporters to lose. And although the inhabitants of Duma are no paupers, underdevelopment and neglect by the government is all too plain to see. “What did we get from Bashar’s supposedly socialist reign apart from private universities?” he ponders, “What about schools and hospitals?” We pass through the illegal settlements where most of the protests take place. The atmosphere at the funeral is somber. Shortly after our arrival, young men begin to form a funeral procession. They shout, “The people demand the proclamation of jihad!” Suleiman A. guesses my thoughts: “We do not want an Islamic Caliphate,” he explains. “But the situation in Duma is much worse than in other places. Every day people are being killed. And this isn’t a demonstration, it’s a funeral.”

Since the beginning of the uprising, the regime has become afraid of funeral processions. Today, dozens of documents have to be obtained from the security forces for a funeral, and, officially, only four men are allowed to follow the coffin. Suleiman A. comments, “Isn’t it strange? We are burying a martyr who was shot and killed during the funeral of a martyr – who in turn was killed during a funeral.”

My clumsily arranged headscarf shows clearly that I am not from Duma, and quickly a crowd of men forms around me. The father of the man killed tells how security forces abducted his son and how his lifeless body was dropped off at the house with a sutured wound lengthwise across the torso. One man draws up his sleeve, another bares his shoulder – both of them show burn marks from electroshock and stubbed-out cigarettes. Then more shots ring out and we have to run. The men follow me running, shouting, “Do remember to write everything down! The observers don’t come to us. You have to write everything down!”

It is night again and our escort wants to return to Damascus, as it would be too dangerous for him to stay in Duma. For months he has been hiding in the fields around Damascus or in the inner city. On the way back, he asks me to visit the hotel where the observers from the Arab League are staying in order to convince them to hear the stories of the activists from Duma-- there is only one phone number for the Arab League’s mission and there is no getting through; as a woman I could easily pretend to be a tourist. I point out that the hotel is guarded by heavily armed security forces and he sighs, laughing, “Observers being observed – so what is there for us to gain?”

In the city center we pass by shops and people sitting in cafés and restaurants smoking their hookahs. I make one last visit with a group of activists and students who have gone into hiding in Damascus. From here, they provide food, medicine and clothes to the battered neighborhoods of the city. “It is not true that nothing is going on in Damascus”, one of them tells me, “It is only the center that is still calm. But Duma for example is almost as bad as Homs.” A young, exhausted-looking man is a member of the Executive Committee of the Revolutionary Council in the city of Homs. He commutes between his workplace in Damascus and Homs and has visited a number of Arab countries to garner support. With its almost parastate structures, the Revolutionary Council is able to assist 10,000 families. Part of its support comes from Syria’s Muslim Brotherhood, part from the business community and other donors. He pours us some wine. “We do need help urgently, otherwise we may become even more dependent on the Muslim Brotherhood. Now Salafi groups abroad are also beginning to offer us support but that is something we do not need.” One member of the group is an Alawite student who has been expelled from university for her political activism. She is helping Alawite families from Homs, supporters of the uprising, who had to take shelter in Damascus. “Within the opposition Alawites are having an especially hard time,” she explains. “For the regime they are traitors, and it deals with them harshly. They are also in trouble within their own community, and the others don’t trust them either.”

Among themselves, the activists discuss taking up arms, something that occupies them more than anything else at the moment. They think that, should the Arab League’s mission be unable to stop the violence, more and more Syrians will be calling for armed resistance. “We do not like to talk about taking up arms, as we need international support. Yet, if such support is not forthcoming, we will be left to our own devices.” They admit that the current stalemate is making them bored. “I’m wearing the same jeans for months and I’m still walking in my summer shoes. The revolution has taken over our lives. How long can we continue like that?” asks a student from Deraa. The army has knocked down his parents’ house in Deraa and his family has fled to Turkey. He remembers the first three months of the revolution as the most emotional and beautiful ones. “We are now entering the anxious phase,” he says, “because the revolution is transforming into armed struggle.”

I ask whether they think that civil war is unavoidable. The student from Deraa says that they cannot tell how everything will turn out. His comrade from Idlib disagrees: “Of course we do know which way things are going – it’s only that we do not want to picture it yet.”

.jpg)

[The author has not used any real names in this piece]

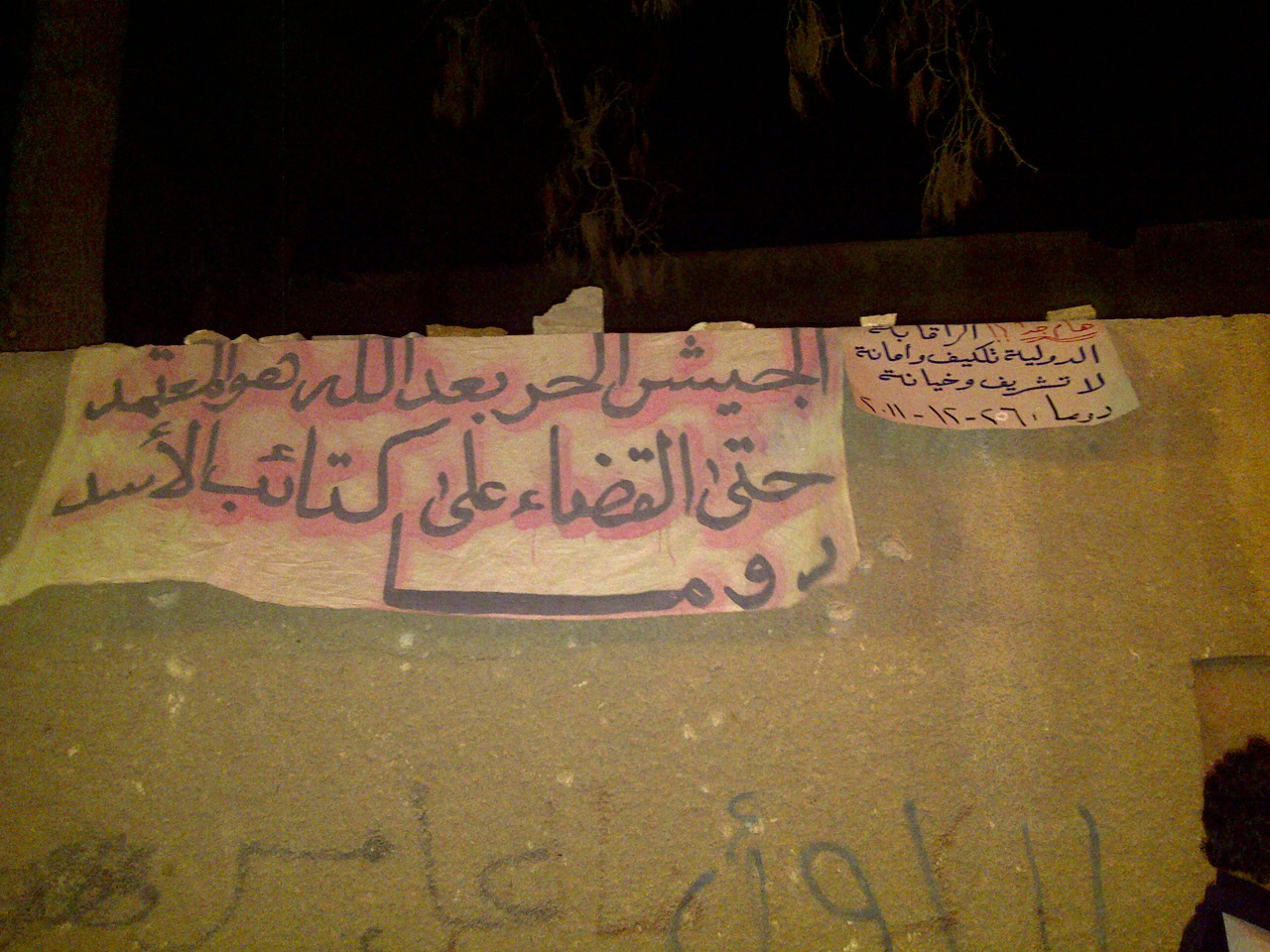

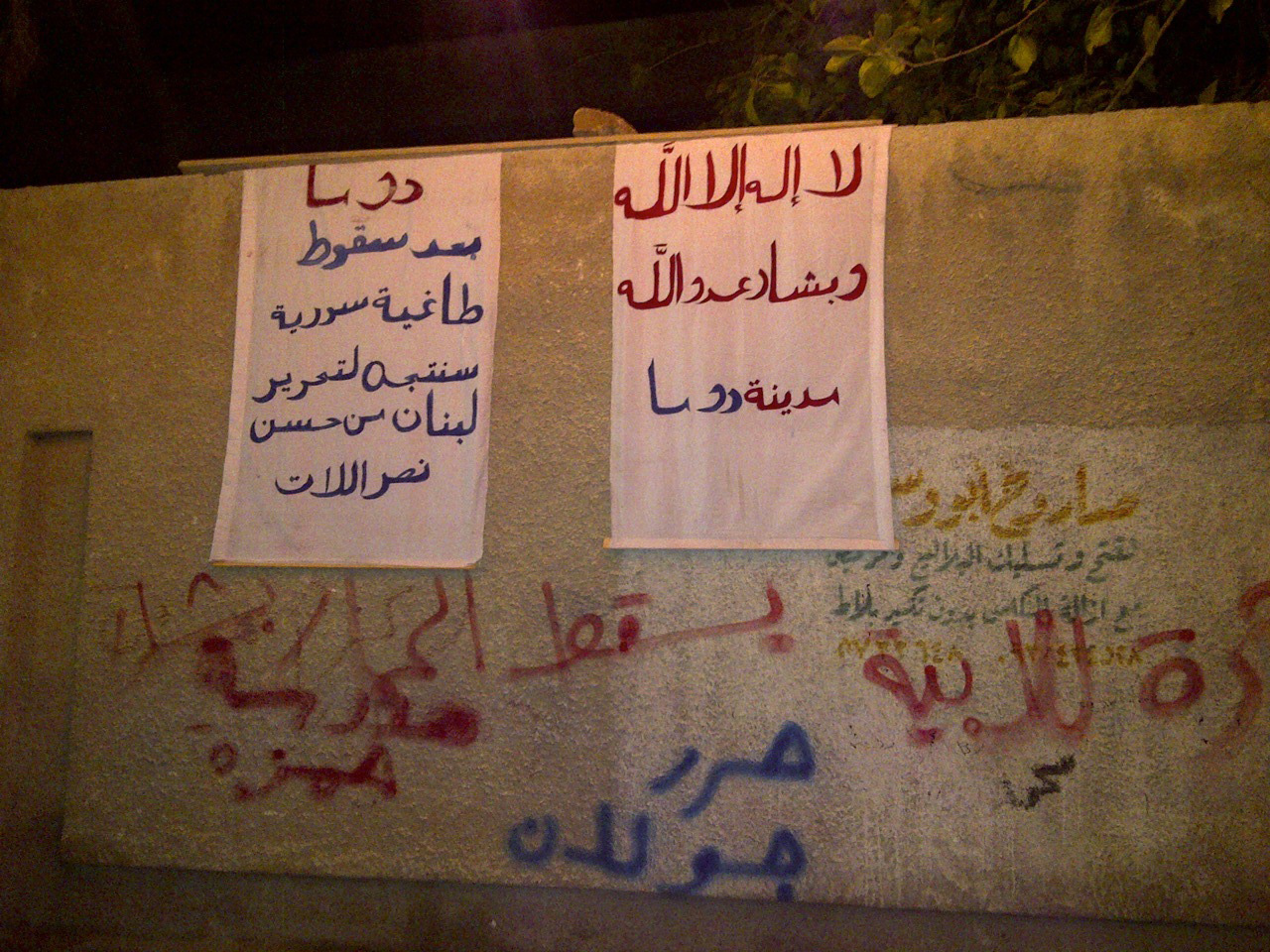

[Images by Layla Al-Zubaidi.]